Recyclable” ≠ “Circular”: Why the Fashion Industry Keeps Getting This Wrong

It says 100% recyclable on the tag. Cool. So... where exactly is it going? Because it’s probably not looping back into a fiber mill. More likely, it’s headed to the same place as the rest of our overproduced, under-worn clothes: landfill, incineration, or some overseas donation bin that becomes another country’s problem.

Here’s the thing — recyclable and circular are not the same. Not even close. And that mix-up isn’t just semantics — it’s stalling real sustainability progress in fashion. One is a material property. The other is a system. And they function very differently in the real world.

Recyclable... in theory

When a brand calls something recyclable, what they’re really saying is: under the right conditions, in the right facility, if everything goes perfectly... this thing could technically be broken down into raw material again. But that’s a hell of a lot of “ifs.”

Most clothing never makes it there. It’s contaminated (food, dirt, makeup), made of blended fibers (like cotton + elastane), or simply not valuable enough to justify the cost of sorting, processing, and recycling. So even if it’s technically recyclable, the infrastructure — and economic incentive — often doesn’t exist to close that loop.

Think about your average polyester workout top. It might say it’s made from “recyclable” fabric. But once you factor in mixed stitching, heat-applied logos, chemical dyes, maybe a little elastane stretch — it’s game over. You’d need a specialized facility to even attempt to recycle it. Most don’t bother.

Circularity is a whole different beast

Circularity isn’t about what could happen to a product. It’s about what actually does.

It’s a system — a loop — where products are designed, collected, and reintroduced into the economy without becoming waste. That could mean resale, repair, rental, fiber-to-fiber recycling, or even composting (for biological materials). But the key is that it happens by design, not by accident.

A circular product isn’t just “made with recycled materials.” It’s made to come back. And that means:

The design anticipates its second life.

The brand has a return or recovery system in place.

There’s infrastructure to process it.

There’s intent to actually close the loop.

Eileen Fisher’s Renew program is a solid example. They take back used garments, sort them, resell what’s wearable, upcycle what’s damaged, and only recycle what they can’t salvage. That’s a circular model. Not perfect, but intentional — and built into their operations.

Here’s where fashion gets it twisted

Brands love to throw “recyclable” on tags because it sounds circular. It’s a quick marketing win — a way to suggest they’re doing something without changing how they operate.

You’ve seen the lines:

“Made with recycled polyester” — okay, but can that polyester ever be recycled again?

“100% recyclable” — great, but do you offer a take-back program?

“Closed-loop collection” — define “closed,” because this loop looks pretty open to me.

The real red flag? When high-volume fast fashion brands brag about using recycled materials, but push out 1 billion garments a year. You can’t scale circularity without systems in place. And mass production of “recyclable” waste is still... waste.

Let’s look at a T-shirt

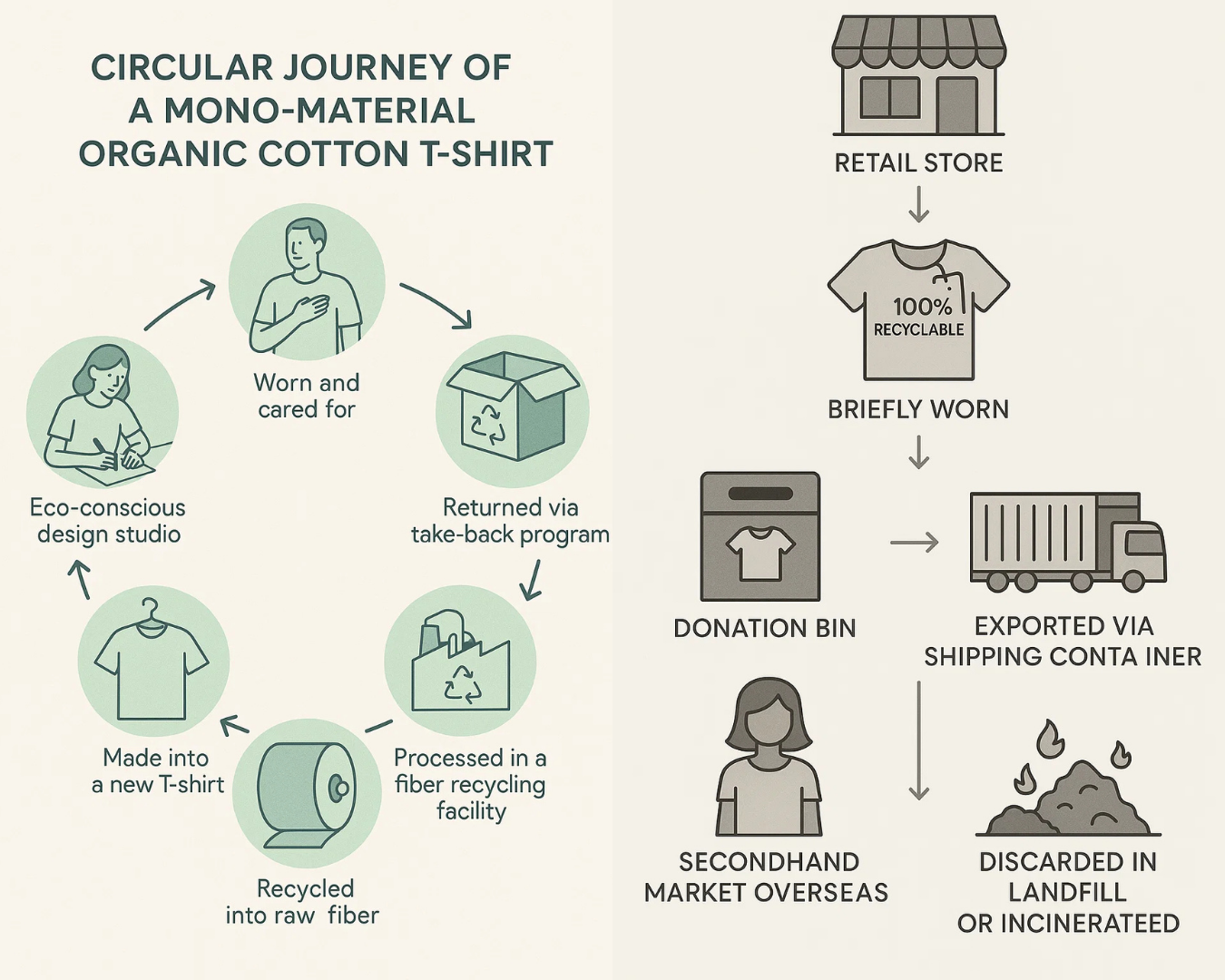

Just to visualize the difference — take two identical-looking tees.

Scenario 1: Recyclable Tee

Made from rCotton and polyester

Worn a few times

Donated (but not resold)

Exported to a secondhand market overseas

Eventually landfilled or burned

Scenario 2: Circular Tee

Made from mono-material organic cotton

Designed for easy disassembly

Returned through a brand’s take-back program

Recycled into raw fiber

Re-spun into a new garment

One is recyclable in theory. The other is circular in practice. And that difference? It’s everything.

When we blur the line between recyclable and circular, we let brands off the hook. We reward superficial claims instead of systemic change. And we lull consumers into a false sense of progress — thinking that tossing a T-shirt in a donation bin equals impact. Circularity is harder. It’s slower. It demands fewer garments, better design, and actual infrastructure. But it’s the only way we get out of this mess with our credibility intact.

So what should we be looking for?

If a brand says their clothes are recyclable, ask:

Do they take them back?

Can they actually process them?

Is there data on what happens after?

True circular systems don’t end at the consumer. They loop back — through reverse logistics, design strategy, and measurable recovery. We don’t need more recyclable clothes. We need fewer clothes, better made — and built to return.