The Recycling Race — Who’s Actually Building the Future of Circular Fashion?

In the last post, we unpacked what textile-to-textile recycling actually is — how it works, why it matters, and all the reasons it’s still not happening at scale. Spoiler: the tech is promising, but the infrastructure is not.

This post is about the people trying to change that.

There’s a whole wave of companies — from biotech start-ups to old-guard engineering giants — trying to build the backend of circular fashion. They’re experimenting with chemical processes, opening pilot plants, signing deals with brands, and quietly trying to solve one of the most complex material challenges in the world.

Some are scaling. Some are stalling. A few have already failed. But taken together, they’re laying the groundwork for what a real recycling system could look like.

I’m not here to hype anyone. What follows is a breakdown of who’s doing what, how they’re doing it, and whether it’s actually moving the needle. We’ll go region by region — mostly because it helps show how uneven this map really is.

Because if textile-to-textile recycling ever does take off, these are the companies that will have made it happen. Or at least tried.

SYRE (Sweden)

Founded:

SYRE was officially launched in 2024 as a joint venture between H&M Group and Swedish investment firm Vargas Holding (the same firm behind Northvolt and Polarium). The goal wasn’t just to fund a recycling start-up — it was to build a global infrastructure company from day one.

Focus:

SYRE is going after one of the biggest challenges in fashion’s material stream: recycling polyester. Not bottles — actual polyester textiles. Their mission is to build massive, industrial-scale recycling plants capable of producing recycled PET (rPET) from old garments and textile waste, not from plastic packaging.

If they succeed, they’d be among the first to create a closed loop system for polyester clothing at commercial scale — replacing virgin plastic with regenerated fiber in a meaningful way. SYRE’s positioning is bold: they’re calling it “textile-to-textile rPET at hyperscale.”

Technology:

SYRE uses glycolysis, an alcohol-based chemical recycling process that breaks down polyester into BHET (bis(2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalate) — one of the base monomers used to make PET. The process is well-established in the bottle industry but hasn’t been widely deployed for textiles, which are more variable and harder to purify. The company is working to optimize the process specifically for fashion waste — including handling dyes, coatings, and material inconsistencies — and is developing its own proprietary system to do it more efficiently than existing players.

Progress:

SYRE is still in early build mode, but they’ve already made major moves. In 2025, they announced plans for a gigascale recycling facility in Vietnam, targeting a capacity of up to 250,000 tonnes per year of recycled polyester. That’s a massive figure, especially in a market where most players are still dealing in the tens of thousands.

What really sets them apart is that they’ve already secured a $600 million seven-year offtake agreement with H&M Group, which guarantees demand for their output. They’re also exploring import licenses to allow the Vietnam plant to source waste from neighboring countries — a critical move in a region where domestic post-consumer textile collection is limited.

Challenges:

SYRE’s biggest challenge will be execution at scale. Building one plant is hard. Building a global network of them — across different geographies, with different regulatory environments, and a deeply inconsistent textile waste stream — is something else entirely. They’ll also need to prove that their process can consistently deliver high-purity recycled polyester from unpredictable textile inputs, and that the economics work not just for H&M, but for future customers too.

Status / Outlook:

Construction hasn’t started yet, but momentum is strong. With deep pockets, a locked-in buyer, and serious industrial ambition, SYRE is probably the most well-capitalized textile recycler in the world right now. But ambition doesn’t equal delivery. Until a plant is running and selling fiber at scale, they’re still just building the runway.

Renewcell / Circulose (Sweden)

Founded:

Renewcell was founded in 2012 by a group of scientists from KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. The idea was simple on paper, but massive in ambition: take old, worn-out cotton clothes and turn them into new cellulosic fiber. Not plastic. Not downcycled fluff. Real fiber input for fashion production.

Focus:

Renewcell focused on cotton-rich textile recycling — particularly garments that were no longer wearable and would otherwise end up in landfill or incineration. Their innovation was called Circulose™, a branded, trademarked material made by breaking down old cotton garments into a pulp that could be used to make viscose, lyocell, or modal — the same way you’d traditionally use wood pulp. They weren’t trying to be a fiber brand — they wanted to become the missing link between fashion waste and regenerated textiles.

Technology:

Their process was a kind of hybrid: part mechanical, part chemical. Garments were shredded, de-trimmed, decolored, and treated to break them down into cellulose slurry, then dried into flat sheets of recycled pulp. No solvents, no plastic processing, no fancy enzymes — just clean material that could drop into existing viscose and lyocell supply chains.

Circulose™ was often described as “recycled cotton in a format mills can actually use.”

Progress:

In 2022, Renewcell opened what was then the world’s first industrial-scale textile-to-textile recycling plant in Sundsvall, Sweden. It was a major moment — not a pilot, not a lab, but a real production facility with the capacity to process 60,000 tonnes of textile waste per year, with plans to double that.

They had high-profile brand partnerships: Levi’s, Ganni, H&M, Zara — all testing or using Circulose™ in small runs. Investors were excited. The press called it a circular breakthrough.

And then… it fell apart.

By early 2024, just five months after the plant went live, Renewcell filed for bankruptcy.

Challenges:

This wasn’t a tech failure. The process worked. But they were crushed by supply chain delays, inconsistent demand, slow uptake from brands, and the brutal economics of trying to compete with virgin pulp.

The reality is, no one was buying enough, fast enough. The industry loved the idea of Circulose, but struggled to integrate it at scale. Brands dragged their feet on commitments. Supply contracts didn’t come in strong enough to support operating costs. And despite early hype, there just wasn’t enough pull-through to keep the model alive. They also had to compete against virgin wood pulp — a cheap, established material with entrenched relationships and pricing power. And they were trying to do all of this in a landscape with almost no policy support and no safety net for failure.

Status / Outlook:

In June 2024, private equity firm Altor bought out Renewcell’s assets and is now relaunching the company under the name Circulose — this time, with tighter focus and (hopefully) better strategic planning.

The pulp still exists. The brand name still carries weight. But whether they can rebuild trust — and secure the contracts and capital needed to stay alive — is an open question.

The takeaway? Tech is not enough. Market readiness, policy, pricing, and patience matter just as much. Maybe more.

Reju (France)

Founded:

Reju was launched in 2023 by Technip Energies, a French engineering powerhouse best known for building oil refineries, gas platforms, and hardcore fossil infrastructure. Yesss — oil refineries. Their pivot into fashion wasn’t random though. It was part of a broader strategy to apply their heavy-duty industrial expertise to green transitions — carbon capture, hydrogen, ammonia… and now, polyester recycling.

Focus:

Reju focuses on chemical recycling of polyester textiles — meaning they’re targeting synthetic clothes, not natural fibers like cotton. Their goal is to break down polyester-rich garments and regenerate them into high-quality raw material that can go straight back into the system. And not just a little: they want to build multiple industrial-scale plants by 2028.

They’re betting on scale from day one — and making it clear that their goal isn’t niche sustainability. It’s full-scale industrial regeneration of polyester.

Technology:

Reju uses a glycolysis process, which means they break down polyester using glycol (a type of alcohol) and catalysts. This process produces a monomer called BHET — the basic building block of polyester — which can then be purified and used to make new polyester again.

A few key things about their method:

Glycolysis is already used in plastic bottle recycling, so it’s relatively well-understood.

Reju’s version is proprietary, developed with IBM and capable of processing blended and contaminated waste.

Their process can handle “your worst stuff” — aka the garbage-quality textiles nobody wants. Think stained poly blends, mixed fibers, landfill-bound junk.

The whole point is maximum funnel width. They’re not cherry-picking perfect garments. They’re aiming to handle the real waste stream.

Progress:

In 2024, they started small — with a 1,000-tonne capacity plant in Germany to test their tech at real-world scale. But they’re already planning two industrial mega-plants in Europe and the U.S., each targeting 100,000 tonnes per year by 2028.

The cost? Estimated at €300 million per plant. The ambition? To build a $2 billion business by 2034.

And unlike many recyclers that struggle with credibility or financing, Reju has something rare: serious engineering credibility and deep corporate pockets.

Challenges:

Let’s be real — this is not cheap. Even Reju’s own CEO said flat out:

That means scaling will depend heavily on:

Policy tailwinds (like recycled content mandates or plastic regulation)

Brand commitments (guaranteed demand to justify upfront capital)

Consumer acceptance (not just of recycled goods, but of synthetic ones that are truly regenerated)

There’s also the fact that polyester itself is controversial. Even recycled polyester sheds microplastics. And while Reju claims its process cuts emissions in half compared to virgin polyester, there’s still energy use, infrastructure buildout, and long-term questions about durability and purity.

Status / Outlook:

Reju’s play is less about winning over sustainability diehards, and more about becoming the industrial default for recycled polyester — backed by tech muscle and policy timing. If they can pull it off, they might become the backbone of Europe’s circular plastics system in textiles.

They’re not promising utopia. They’re promising better polyester — and a system that can actually deliver it.

Infinited Fiber Company (Finland)

Founded:

Infinited Fiber Company was established in 2016 in Finland, emerging from research conducted at the VTT Technical Research Centre. The company is co-founded by Petri Alava and Ali Harlin, with a mission to transform textile waste into high-quality, circular fibers.

Focus:

The company specializes in converting cotton-rich textile waste into a regenerated fiber called Infinna™. This fiber mimics the look and feel of cotton and can be used alone or blended with other fibers, offering a sustainable alternative to virgin materials.

Technology:

Infinited Fiber's patented process involves breaking down cellulose-based materials like cotton into a pulp, which is then treated chemically to create a regenerated fiber. The resulting Infinna™ fiber is biodegradable, contains no microplastics, and can be recycled alongside other textile waste, promoting a circular economy.

Progress:

The company has garnered significant attention and investment, including a €30 million Series B funding round in 2021, with investors like Adidas, Bestseller, and Zalando. Infinited Fiber has also entered into multi-year partnerships with brands such as PVH Europe and Inditex. Plans are underway to build a flagship factory in Kemi, Finland, with an annual production capacity of 30,000 metric tons, expected to commence operations in 2026.

Challenges:

Scaling production to meet global demand remains a hurdle. Additionally, integrating Infinna™ into existing supply chains requires collaboration with brands and manufacturers to adapt to new materials and processes.

Status / Outlook:

With strong backing and strategic partnerships, Infinited Fiber is poised to play a significant role in the future of sustainable textiles, offering a viable solution to reduce reliance on virgin cotton and decrease textile waste.

Worn Again Technologies (UK)

Founded:

Worn Again Technologies was founded in 2005 in East London, UK, by Cyndi Rhoades. The company aims to eliminate textile waste through innovative recycling technologies.

Focus:

The company focuses on developing a closed-loop chemical recycling process that can separate and recapture polyester and cellulose from non-reusable textiles, including polycotton blends. This technology enables the production of new fibers from old textiles, reducing the need for virgin resources.

Technology:

Worn Again's proprietary process involves separating, decontaminating, and extracting polyester and cellulose from end-of-use textiles. The dual outputs—recycled PET and cellulose pulp—can be reintroduced into the supply chain to create new textiles, supporting a circular economy.

Progress:

The company has established a demonstration plant in Winterthur, Switzerland, capable of processing up to 1,000 tons of textile waste annually. Worn Again has also joined the Alliance of Textile Chemical Recyclers (ACTR), collaborating with industry leaders to promote chemical recycling solutions. Strategic investors include H&M Group, Sulzer Chemtech, and Oerlikon, among others.

Challenges:

Transitioning from demonstration to commercial-scale operations is a significant challenge. Additionally, the company must navigate regulatory landscapes and secure long-term partnerships with brands to ensure consistent demand for recycled materials.

Status / Outlook:

Worn Again is in the scale-up phase, working towards commercializing its technology and expanding its impact on the textile recycling industry. With strong partnerships and a clear vision, the company is well-positioned to contribute to a more sustainable future for fashion.

Circ (USA)

Founded

Circ was founded in 2011 and is based in Danville, Virginia. Originally working in waste-to-energy, the company pivoted to textile recycling — and that pivot turned out to be their breakthrough.

Focus

Circ’s focus is on circularity for blended textiles — the trickiest kind of textile waste. Their tech is specifically designed to handle polycotton blends (which make up a massive portion of fashion waste) and separate them efficiently so each component can be recycled independently. The goal? Turn a landfill-bound T-shirt into high-quality raw material for another.

Technology

Circ uses a hydrothermal process (water, pressure, heat, and proprietary chemistry) to break apart polyester and cotton. Unlike traditional recyclers that rely on clean or mono-material input, Circ’s tech can handle messier feedstock — real-world garments, not just factory cutoffs.

Once separated, the cotton is pulped into cellulosic fiber (which can be spun into viscose or lyocell), while the polyester is chemically depolymerized into TPA, a building block for new polyester. It’s a closed-loop approach with minimal waste.

Progress

Circ has secured significant backing from major fashion players, including Zara-owner Inditex, and is currently working on building its first industrial-scale facility in France, expected to be operational by 2028. That plant aims to process 70,000 tonnes of feedstock per year.

They’ve also partnered with brands like Zara and Puma to test Circ-derived textiles in real products — a critical step for validating both tech and market appetite.

In 2025, Circ’s president called their upcoming plant a “tipping point” for circular fashion — framing it not just as company progress, but a system-wide milestone.

Challenges

Despite impressive tech, Circ still faces the same system issues as everyone else: securing feedstock, navigating global supply chains, and managing costs.

They’ve focused first on post-industrial waste (factory offcuts) because it’s more consistent and less contaminated — a smart move, but not the holy grail. Their long-term goal is to pivot to post-consumer waste, which will require stronger sorting infrastructure and broader textile collection policies, especially in North Africa and Europe where the French plant will operate.

Evrnu (USA)

Founded

Evrnu was founded in 2014, headquartered in Seattle. They positioned themselves early as a science-driven innovator aiming to rethink the entire textile-to-textile recycling value chain — not just create a product, but rewrite the materials game.

Focus

Evrnu focuses on taking waste cotton garments and transforming them into entirely new engineered fibers that outperform virgin cotton. Their vision is to design superior materials using recycled inputs — it’s not just about circularity, it’s about performance and value.

Technology

Their core innovation is a technology platform called NuCycl. It chemically converts post-consumer cotton waste into a regenerated cellulosic fiber. The final fiber can be tuned to perform like cotton, silk, or synthetic blends, depending on need — giving it versatility most recycling tech doesn’t offer.

What sets NuCycl apart is its closed-loop capability: the material can be recycled multiple times without significant degradation in quality. That’s rare — most textile recycling is a one-and-done deal.

Progress

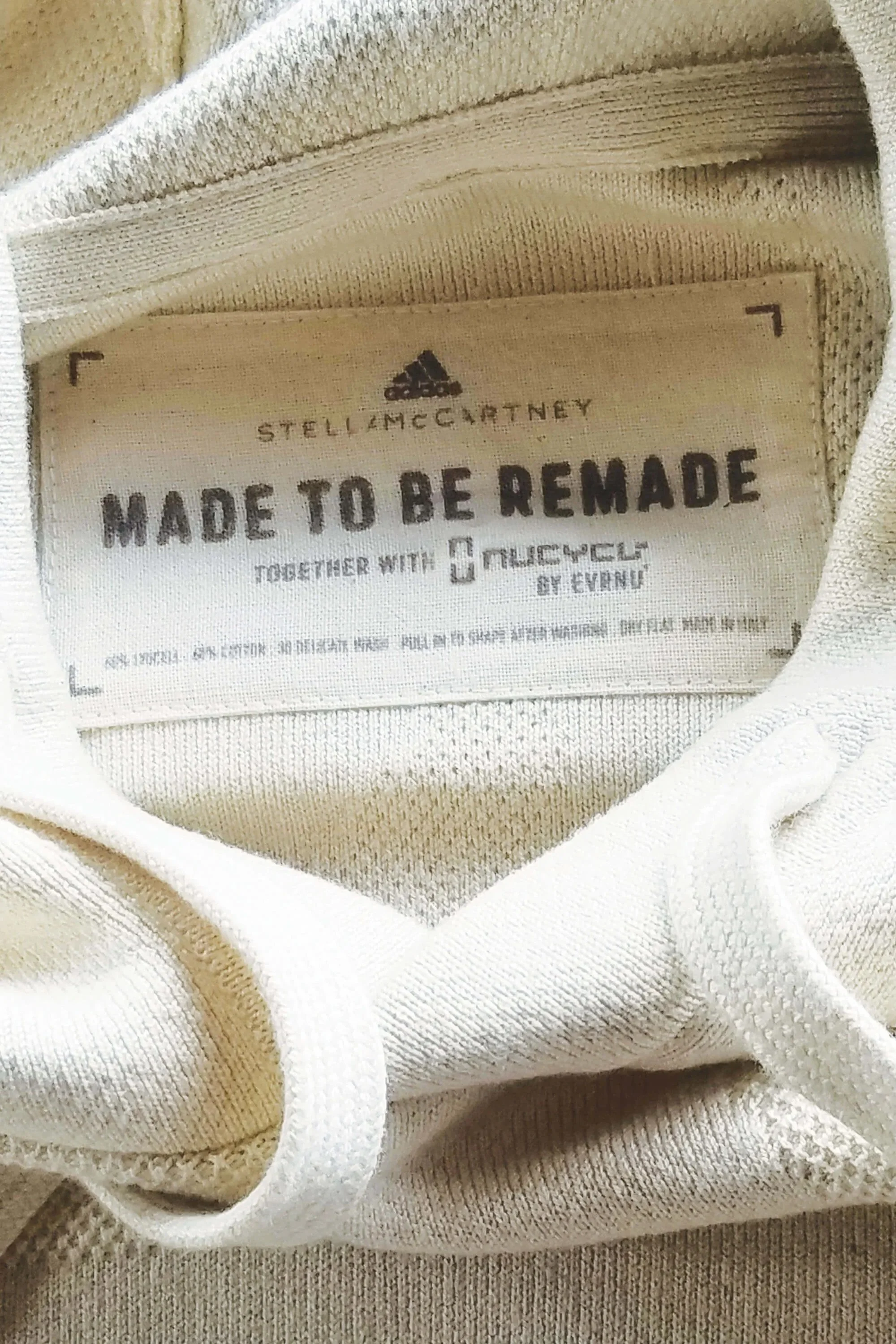

Evrnu has secured major partnerships with Stella McCartney, Adidas, and Target, among others. They’ve also been involved in early capsule collections to showcase NuCycl’s quality — proof that their product is commercially viable, not just a lab dream.

Their pilot facility is already operational in the U.S., and they’re scaling up through licensing models — offering their technology platform to mills and manufacturers rather than trying to build massive facilities themselves. It's a flexible, capital-light strategy to go global faster.

Challenges

Evrnu’s challenge lies in infrastructure alignment. Their product is legit — but to get enough clean, high-quality cotton waste to feed their process at scale, they need global systems that don’t exist yet. They’re banking on sorting partnerships and upstream collaboration to get there. And like every other innovator, they still face cost pressures. Chemical recycling is expensive, and while Evrnu’s value prop is strong, widespread adoption will require big brand commitment and likely regulation to level the playing field.

Ambercycle (USA)

Founded

Ambercycle was founded in 2015 in Los Angeles by two young scientists straight out of college. The original goal? Build a better way to recycle clothing. Over time, that vision matured into a sharp focus: converting end-of-life garments, especially synthetics, into circular raw materials for the fashion industry.

Focus

Ambercycle is laser-focused on polyester, the dominant material in fashion and one of the hardest to recycle. Their pitch is simple but bold: a fully circular system where polyester garments are broken down and rebuilt into new, high-quality polyester — again and again.

They’re not just recycling; they’re regenerating materials into a premium product brands can trust.

Technology

Ambercycle’s signature tech is called cycora® — a regenerated polyester made from post-consumer textile waste, not plastic bottles. This distinction matters. While most “recycled polyester” today comes from bottles, cycora® is actually made from old clothes, which is what real circularity demands.

Their chemical recycling process breaks polyester down into its base monomers, purifies it, and rebuilds it into new yarn. The output is molecularly identical to virgin polyester — but with a drastically smaller footprint. Think 75% lower CO₂ emissions, according to their internal claims.

Progress

They’ve already launched commercial drops using cycora®, including partnerships with brands like Adidas (notably in their Made To Be Remade line) and Ganni. These aren’t just one-off PR stunts — cycora® is being integrated into real product lines.

In 2023, they raised $21 million in Series A funding, with backing from H&M and Zalando, among others. The capital is being used to scale their commercial recycling facility in LA, with ambitions to process tens of thousands of tonnesannually.

Challenges

Ambercycle’s tech is solid, but like everyone else in the space, they face a scaling problem. Securing consistent, clean feedstock for polyester recycling is not easy — especially because most clothes are blends, and most sorting systems aren’t built for fiber-level purity. On top of that, price parity with virgin polyester is a hurdle. cycora® is premium, but fashion still runs on cost margins. Ambercycle is betting that regulation, consumer pressure, and brand ESG targets will force a shift toward circular sourcing — making their pricing more competitive over time.

Natural Fiber Welding (USA)

Founded

Natural Fiber Welding (NFW) was founded in 2015 in Peoria, Illinois, by materials scientist Dr. Luke Haverhals. The original goal wasn’t just to solve textile waste — it was to reinvent the materials we use altogether, from the ground up. Less “recycling problem,” more “rethink the inputs.”

Focus

Unlike most textile recycling companies, NFW isn’t focused on breaking things down and rebuilding them. Their model is fundamentally additive, not subtractive. They’re focused on replacing plastics entirely with natural, circular alternatives — materials that can be regenerated without petrochemicals, toxins, or microplastic pollution.

Their main target? Animal leather and synthetic leather. Instead of plastic-based “vegan leathers,” NFW is building high-performance natural alternatives made from plants and agricultural waste — and doing it at industrial scale.

Technology

Their hero product is MIRUM®, a leather-like material made entirely from natural ingredients: things like rubber, cork powder, rice hulls, coconut husk fiber, and plant oils. No petrochemicals. No PU coatings. And crucially: no plastic whatsoever.

They also produce CLARUS®, a process that strengthens and welds natural fibers like cotton into high-performance textiles — without synthetics. Think of it as an upgrade for natural fabrics, rather than a workaround.

The kicker? Both products are closed-loop by design — they can biodegrade at end of life or be broken down and reused within the system.

Progress

NFW is already in-market with major brands. Allbirds, Ralph Lauren, BMW, and Stella McCartney have all partnered with them on MIRUM® applications — from sneakers to steering wheels.

In 2022, they closed a $85 million Series B round, with investments from BMW i Ventures, Ralph Lauren Corporation, and Allbirds. They’ve also opened a scalable manufacturing facility in Illinois and have plans to ramp up production further to meet growing demand.

In a space full of lofty claims, NFW is delivering at scale — and doing it without synthetic shortcuts.

Challenges

Their biggest challenge is arguably changing entrenched mindsets. MIRUM® is not “like leather,” it’s its own category — which can be both a marketing hurdle and a regulatory gray zone. Brands often don’t know how to position it. There’s also the complexity of supply chains. Scaling up natural inputs while keeping them traceable, consistent, and cost-competitive requires serious agricultural coordination, especially if they want to stay truly regenerative and local. Still, NFW is one of the only players in the space with a fully plastic-free, scalable, circular material — and they’re just getting started.

Final Thoughts: The Roadblocks No One Can Ignore

So we’ve got the tech. We’ve got the ambition. And we’ve got the brand partnerships that make headlines. But here’s the thing: if you zoom out, it still feels like the recycling revolution is stuck in beta mode.

Are We Scaling or Just Piloting?

Every company we just profiled is trying to reach industrial scale — or at least claim they're on the way. And yes, it’s a big deal that they're raising capital, signing offtake agreements, and building real factories. But when you look at the numbers, even the most promising plants (like Reju or Circ) are aiming for 50,000–100,000 tonnes of capacity. That’s a drop in the ocean when the world tosses out over 90 million tonnes of textiles every single year. This is not industrial scale. This is still proof-of-concept.

Feedstock: The Elephant in the Room

Even if the tech works flawlessly, these facilities need a ridiculous amount of raw material just to run. And that’s where things start to get messy. Recyclers can’t function without a steady stream of sorted, clean, specific types of waste. But most cities don’t have the collection systems. Most brands don’t have the traceability. And no one really knows how to get all that “waste” moving through the system in a way that’s consistent, legal, and scalable. Everyone’s talking about tech. But feedstock might be the real bottleneck.

Tech Is Ready. Systems Are Not.

One of the wildest things here is how advanced some of this recycling science actually is. These companies are pulling off complex chemical reactions, working with enzymes and microwave catalysts and precision sorting that sounds like sci-fi. But none of that matters if the broader system can’t support it. The sorting infrastructure doesn’t exist. The policies are still in early innings. And even though brands are eager to make public-facing commitments, most haven’t figured out how to integrate these materials into their actual supply chains at scale — without cost blowouts or production delays.

Tech is not the issue anymore. Systems are.

So… What Would Success Even Look Like?

Let’s be honest. The dream scenario — fully circular fashion at mass scale — is still far, far away…

But success doesn’t have to mean perfection. Right now, progress looks like:

Building sorting and logistics systems that actually work

Creating policy that supports (and subsidizes) recycling infrastructure

Getting brands to lock in long-term contracts and build true pull-through demand

Making recycled inputs competitive without needing PR hype to carry them

That’s the real bar.

And maybe the final point here: recycling is not the finish line. It’s not the answer to overproduction, or overconsumption, or the business model problems fashion refuses to confront.

But if we want to do better with the waste we’ve already created — and stop making things worse — this matters.