SASB — The Framework That Knew Fashion Wasn’t Tech

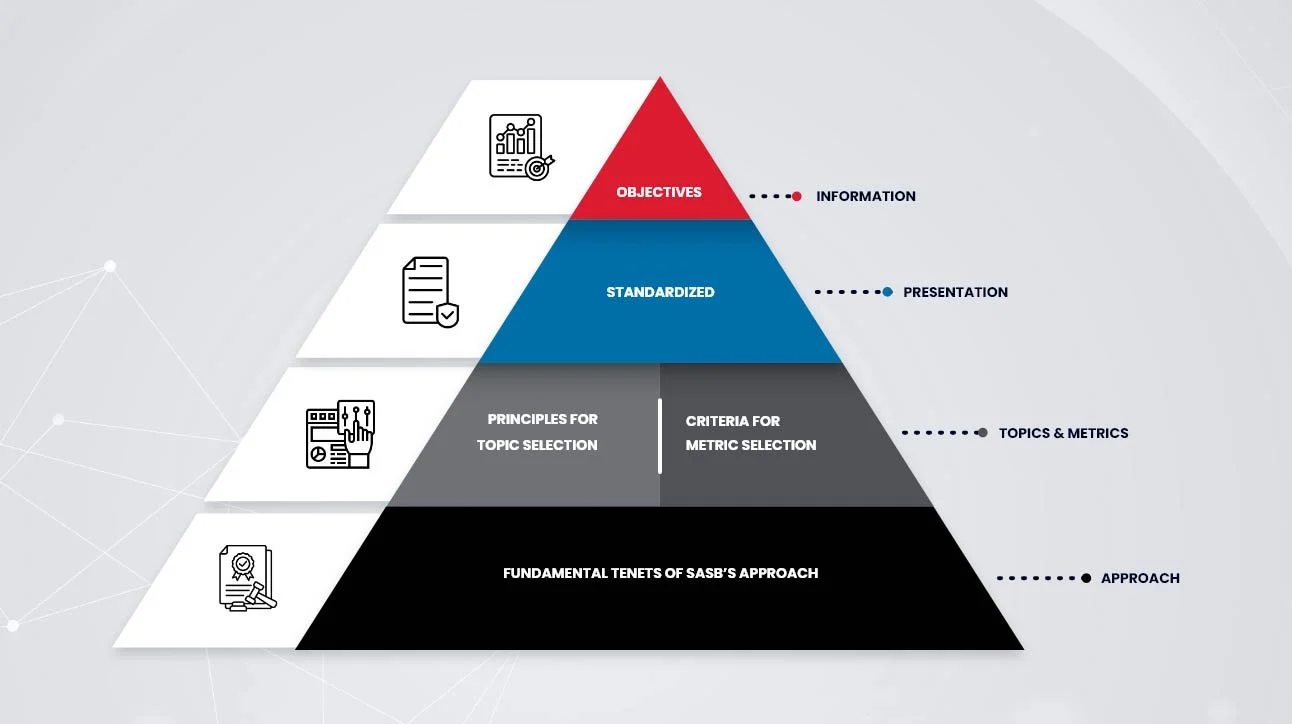

SASB Framework

Before sustainability reports became 90-page PDFs filled with nature photos and airy goals, SASB was trying to get companies to answer a much more practical question:

“What sustainability risks actually matter to your business — and are you reporting them?”

That was it. No grand mission statements. No social media green flexing. Just investor-focused, sector-specific disclosure. And in an industry like fashion, where material risks are everywhere, SASB was one of the first to actually name them.

So what is SASB?

SASB stands for the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. It launched in 2011 as a U.S.-based nonprofit with one clear goal:

Create a standardized set of ESG disclosure metrics for every major industry — so investors could stop reading between the lines.

Unlike frameworks that treat sustainability as a single, catch-all topic, SASB recognized early on that every industry carries different risks.

A mining company faces one type of exposure. A tech firm faces another. And fashion? Fashion’s got its own mess — water, labor, raw materials, reputational fallout.

SASB took that seriously and built tailored standards to match.

Why does it exist?

At the time, ESG investing was growing fast — but the data was chaos.

One company disclosed Scope 1 emissions.

Another mentioned water use but didn’t quantify it.

Most just dropped vague goals in their CSR reports and moved on.

SASB was created to fix that — to bring consistency and comparability to ESG disclosures, especially for financially material issues. Not feel-good stats. Not marketing copy. Just the stuff that could move share price or impact operations.

What did SASB actually ask for?

SASB published industry-specific standards for 77 sectors. Each one included:

A list of material sustainability issues

A rationale for why they’re financially relevant

Recommended disclosure metrics — both qualitative and quantitative

For Apparel, Accessories & Footwear, SASB focused on:

Raw material sourcing risks (e.g. cotton, leather, synthetics)

Labor practices in the supply chain

Water use in dyeing and finishing

Waste and packaging

Energy use and emissions

Data privacy (for D2C brands)

What made it work is that it didn’t overreach. SASB didn’t ask companies to save the planet — it asked them to disclose, clearly and consistently, on things that had actual financial consequences.

Who actually used it in fashion?

More than you’d think — especially in the U.S. and among public companies:

PVH Corp (Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger) — one of the earliest adopters

Nike — included SASB-aligned metrics in annual and ESG reports

Lululemon — aligned its sustainability and risk disclosures with SASB

Kering — used SASB alongside TCFD and GRI in investor communications

These brands weren’t just doing it for fun. SASB became a quiet gold standard for investor-facing ESG reporting, especially in the pre-ISSB years.

Was it enforced? Not really.

SASB was always voluntary. There was no certification, no scoring, no watchdog. But investor pressure made it feel mandatory. ESG rating agencies, asset managers, and analysts all started expecting SASB-style disclosures — and flagged companies that didn’t provide them. For public companies, especially in the U.S., not using SASB was starting to look like a red flag.

Why did it matter for fashion?

Because fashion’s risks don’t look like tech’s. Or finance’s. Or oil and gas.

SASB was one of the few frameworks that said:

“Hey, raw material volatility, labor ethics, and water scarcity are real risks for your business — and you need to talk about them.”

It gave brands a language to talk about:

Why cotton price shocks matter

Why child labor allegations can affect shareholder value

Why wastewater regulations could impact margin

Why supply chain breakdowns aren't just ethical — they’re operational threats

In short, SASB helped translate sustainability into business risk, in a way that made sense to CFOs and investors.

So what happened to it?

In 2021, SASB merged into the ISSB — the International Sustainability Standards Board — which is now building the global ESG disclosure baseline.

But SASB isn’t dead. Far from it.

Its industry-specific standards are still in use — and still referenced

ISSB is literally using SASB as the foundation for its sector-based guidance

Brands that say they’re aligning with ISSB are, in many cases, just using SASB under a new name

It’s the same logic. Same metrics. Just evolving into a global framework.

Any drawbacks?

Yeah, a few — and they’re worth being clear about.

SASB focused on financial materiality only — meaning it prioritized what matters to investors, not necessarily what matters to communities, ecosystems, or supply chain workers

It didn’t push hard on double materiality, like the EU’s ESRS now does

It had limited enforcement, which meant brands could cherry-pick disclosures or just go through the motions

It was U.S.-centric in tone and structure — sometimes clunky for global operations

But even with all that? It still did more to advance real, relevant ESG disclosure in fashion than almost any other framework at the time.

What now?

SASB lives on — through ISSB, through investor reports, and through the way brands now structure their ESG strategy. Whether companies name-drop it or not, they’re still using its bones. If you want to know what sustainability issues fashion brands actually have to face — and what investors care about seeing — SASB is still the blueprint.