WTF is an LCA? And Why It Actually Matters in Fashion

The Buzzword No One Actually Understands

At some point, “LCA” became one of those sustainability acronyms people just drop into conversation like everyone knows what it means. Like, “Oh, we based this on an LCA” — cool, great. But… what’s in it? Who made it? What does it measure? No one really says. And most people nod along like they get it. Here’s the thing though: LCA = life cycle assessment. It’s the behind-the-scenes tool that tells you how “sustainable” something actually is. Not in theory, not in vibe — but in numbers.

If you’ve ever seen a claim like “this has 60% less impact” or “70% fewer emissions,” there’s probably some kind of LCA (or part of one) behind it. That’s how brands get those stats. That’s how climate targets get tracked. That’s how Scope 3 emissions even get calculated in the first place.

So if we’re going to talk about sustainability seriously — in fashion or anywhere else — we kind of need to know what an LCA actually is, what it’s trying to do, and where it sometimes falls apart. This isn’t going to be a technical deep dive. It’s more of a reset. Like:

Here’s what LCA was meant to be. Here’s how it gets misunderstood. And here’s how fashion brands could be using it better.

So… What Is an LCA, Really?

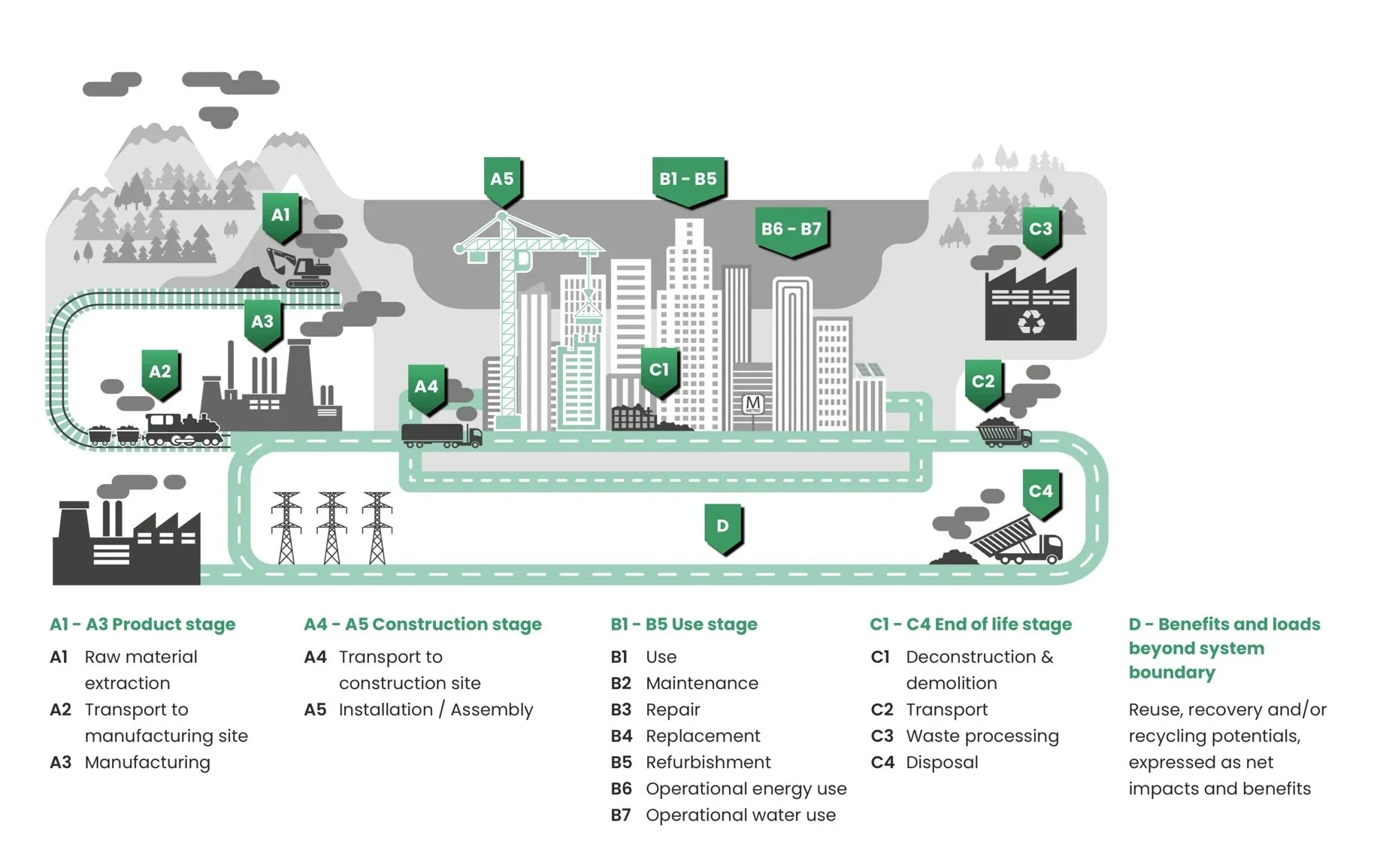

A life cycle assessment is basically a tool that measures the total environmental impact of something — from start to finish. That “something” could be a t-shirt, a handbag, a building, a material… anything that gets made, used, and eventually thrown away or reused.

The idea is: if we want to reduce our impact, we need to first understand where that impact is actually happening.

Not just “in the factory,” not just “because it’s plastic” — but across the whole timeline:

Where the raw materials came from

How much water or energy was used

What emissions were created

How people use the product

And what happens to it at the end

So LCA is basically a way of following a product’s life — from raw material, to production, to transport, to use, to disposal — and mapping out what that process takes from the planet (resources, energy) and what it leaves behind(waste, pollution, carbon emissions, etc.). Sometimes it’s called “cradle to grave.” Other times, if it only covers part of the cycle, it’s “cradle to gate” (just up to the factory door). Either way, it’s supposed to give us a clearer picture of what’s actually going on behind a product — not just what it looks like on a hangtag.

That’s what LCA was built for.

To replace guesswork with actual data.

Why LCAs Matter — And Where They Show Up in Fashion

Most of the stuff that gets labeled “sustainable” in fashion has a backstory. Someone had to decide what that meant. Someone had to do the math — or at least try to. That’s where LCA comes in.

Even if the term isn’t printed on the tag or spelled out on a brand’s website, LCA thinking is usually baked into the claims you’re seeing:

This product has 30% fewer emissions

We’ve reduced water usage by 60%

Our recycled nylon has a lower impact than virgin

None of those numbers come out of thin air. They’re either based on actual LCAs (run in-house or by a consultant), or pulled from bigger databases that use LCA data to estimate the impact of certain materials.

LCA also shows up behind the scenes — in things like:

Scope 3 emissions reports (aka all the carbon that happens outside the company walls)

Material sourcing decisions (which fiber has lower water use? which dyeing process emits less?)

Science-based targets (to meet climate goals, companies need to prove where emissions are dropping)

It’s not just a research tool. It ends up influencing what gets made, how it’s marketed, and how brands report progressto the public, their investors, or regulators. Which is why it’s so important to understand what LCA can do — and also what it can’t.

Where LCAs Get Misused — and What You Should Watch For

On paper, LCA sounds airtight. Measure the full impact of a product, make better decisions, done. But in practice? It gets a bit murky. And in fashion, that murkiness can get turned into marketing pretty quickly.

Here’s where it tends to fall apart:

Cherry-picking the good parts

Not every LCA looks at the full life of a product. Some stop at the factory door. Others leave out the customer use phase (washing, drying, etc.). Some ignore what happens when the product is thrown away. That’s not always shady — sometimes there’s just no data — but if a brand is only showing the low-impact part and not the full picture, that’s something to watch.

Only showing carbon numbers

CO₂ emissions are important. But impact isn’t just about climate. What about water use? Toxic chemicals? Land degradation? If an LCA only shows carbon, it might be missing other serious issues — especially in materials like cotton or leather that have big water and land impacts.

No context or comparisons

“50% less impact” — compared to what? Last year’s collection? A completely different material? A fake baseline? If you can’t tell what the original number was, or what the new one is, the stat doesn’t mean much.

Assumptions that never get explained

Every LCA involves choices — where the data came from, what regions it covers, what kind of energy mix is being modeled. Those choices affect the results. If none of that is disclosed, you have no way of knowing how reliable the final number is.

Making big claims off someone else’s data

Sometimes brands use numbers from a database or someone else’s LCA — like saying recycled polyester has a lower impact because that’s what the chart says. But unless that data matches their product, their supply chain, theirfactories… the claim doesn’t really hold.

The point isn’t that LCAs are bad. They’re not. The point is that they’re complex. And when that complexity gets stripped away — for a billboard, a campaign, or a sustainability page — we lose the ability to ask better questions.

So What? Why This Actually Matters

It’s easy to assume that things like life cycle assessments, carbon footprints, and emissions categories are for technical teams to figure out. And sometimes they are. But LCA thinking is already influencing the products that get made, the materials that get chosen, and the way sustainability is communicated to the public. You don’t need to be an expert. But it helps to know what this tool is, what it can do, and where it has limits. Most of the time, it’s not about proving something is perfectly sustainable. It’s about understanding tradeoffs — and making those tradeoffs visible. LCA helps people see where the real impact is happening, and where change might be possible.

That’s the value.

Not perfection. Just clarity.